Father-Child Relationships Following Divorce

Dr. Gordon E. Finley

The question facing both fathers in particular and society as a whole at the dawn of the twenty-first century is: Are fathers to be - or not to be - a part of the human ecology of children? Unprecedented and conflicting changes have occurred in the American family over the past half century that have transformed father-child relationships and our expectations for the role of fathers in their children’s lives. In the 1950s, both the divorce rates and the rates of unmarried motherhood were low, and as a consequence fathers reasonably could count on continuing contact with their children throughout the adult life-cycle. Beginning in the 1960s, however, the American family has undergone radical transformations, which continue today. The social context has changed to the extent that some feminists have declared fathers to be non-essential (Silverstein and Auerbach 1999). For some, America has gone from “father knows best” to father is nonessential.

Many family forms are present today in large numbers that were infrequent in the 1950s. In recent years, the percentage of children born to mothers who were not married at the time of delivery has hovered around 33 percent; the first-marriage divorce rate around 50 percent, the permanent separation rate around 17 percent; and the step-family divorce rate around 60 percent (Hetherington and Stanley-Hagan 1997). What is of critical importance to society is that in virtually all of these events, it is the father-child relationship that is marginalized or severed. Of perhaps equal importance is the reality that this marginalization and severing of father-child relationships comes at the same time that nurturant father involvement in the lives of their children has become an issue of national concern (Braver and O’Connell 1998; Farrell 2001; Knox 1998; Parke and Brott 1999).

The father-child relationships of children born to never-married mothers is tenuous, and in any case beyond the scope of this article, which focuses on the consequences of divorce for children and fathers. The most powerful determinant of father-child relationships following divorce are the policies and practices of the family court system, which awards either sole custody or primary residential parental responsibility to the mother around 85 percent to 90 percent of the time. Fathers generally are awarded “visitation” - a term abhorred by father advocates, who view visitation as structuring the role of the father as a visitor in his child’s life rather than as a meaningful parent. What this means for fathers and children is that they are living in different residences and see each other on a limited and fixed visitation schedule, which is determined by the courts or negotiated “in the shadow of the law”. Thus, what was formerly daily father-child contact in a shared residence now becomes infrequent contact on a fixed schedule, with father and child living in different residences. Under these court mandated circumstances, the father-child relationship is at greater risk of being marginalized or severed than is the mother-child relationship, since mothers and children continue to share a residence and have daily contact.

The risks of negative consequences for fathers and children as a result of the marginalization or severing of the father-child relationship with divorce appear to be substantial for both fathers and children. An early review of the literature (Thompson 1994) provides one of the best discussions of the issues to date. Ross Thompson’s lasting contribution was to focus on the division of the intangible assets of a marriage, the emotionally meaningful relationships between the former spouses and their offspring. While much of the dominant discourse on divorce at that time tended to focus on the division of the tangible assets of divorce (primarily financial assets), Thompson had the foresight to focus on the emotional relationships between former spouses and their offspring, as well as the long term impact of these relationships on the lives of fathers and children.

Consider first the consequences of divorce for fathers (Amato 2000; Braver and O’Connell 1998; Knox 1998; Parke and Brott 1999; Thompson 1994). Compared to mothers of divorce, fathers of divorce have higher - and often substantially higher - rates of: suicide, depression, alcohol abuse, drug abuse, poor health, work problems, relationship problems, and social isolation. Although numerous explanations for these negative outcomes for fathers have been proposed, those favored by father advocates focus on the loss of meaningful contact with their children. The core argument here is that postdivorce father-child relationships are of critical importance not only for the well-being of children, but also for the well-being of fathers. Additionally, some of these negative outcomes for fathers also likely stem from the changing role expectations for fathers that began in the mid-1970s. Beginning in the mid-1970s, fathers were increasingly expected by society to be involved in nurturing their children. At the same time, however, the opportunity structure for the fathers’s nurturing involvement with his children was decreasing, due to increasing rates of divorce and unmarried motherhood. Such a conflict between changing role demands and changing opportunity structures hardly can be conducive to either fathers’ or children’s physical or mental health.

For children, the consequences of divorce are commonly negative. The most significant exception is that divorced children from high-conflict marriages fare better than children who remain in high-conflict intact marriages. The negative consequences for children of divorce, as compared to children of intact families, are immediate, short-term, and long-term. Although there currently is intensive debate in the scholarly literature regarding the magnitude and subtlety of these negative effects, there nonetheless is substantial evidence to suggest that the consequences for children of divorce are present and pervasive, and that they include higher levels of academic problems, a higher rate of dropping out of high school, conduct problems, poor psychological adjustment, psychological distress, poor self-concept, low social competence, precocious sexual activity, teen pregnancy, alcohol and drug use, long-term negative health consequences, and relationship difficulties in adolescence and adulthood (Amato 2000; Booth 1999; Emery 1999). There also is a growing realization that divorce does not affect all parties in the same way. Outcomes of divorce are mediated and moderated by a variety of factors inherent to different families, different children, different fathers, and different mothers, as well as by their social and economic context. Indeed, very recent longitudinal studies suggest that some of the negative outcomes of divorce for children formerly attributed to the act of divorce are manifested prior to the event of divorce. In short, the picture is complex and evolving.

While the consequences of divorce for the father-child relationship can be viewed from many different perspectives, the perspective least explored focuses on the voices of children of divorce themselves. One view comes from the longer-term, retrospective perspective of adult children as they look back on how they wished things might have been in their relationships with their fathers - their perceptions of the wants, regrets, and missed opportunities of father involvement caused by divorce. In a recent study (Finley and Schwartz 2001), a colleague and I asked children of both intact and divorced families “What did you want your father’s level of involvement to be compared to what it actually was?” The critical results demonstrated that, as compared with adult children of intact families, what adult children of divorce wanted most from their fathers was companionship, sharing activities, leisure/fun/play, providing income, emotional development, and caregiving. What was most important to children of divorce were the emotionally meaningful intangible assets lost through divorce (Thompson 1994) - the “being there” assets of affection, emotional connection, and companionship with their fathers. If fathers and children are to be spared the suffering that goes with the current situation, then changes must occur in social attitudes, social policies, and social practices that reinvigorate the father-child relationship following divorce.

There are many changes that have the potential to enhance father-child relationships, including (1) restructuring the divorce industry to provide equal opportunity for both fathers and mothers to maintain meaningful postdivorce relationships with their children; (2) replacing the inherently adversarial family court system with one based on a vision of divorce as a social service rather than a legal service; (3) changing the dominant discourse on divorce to emphasize the research findings that show fathers and mothers to be equal in their parenting skills and capacities; and (4) reducing the use of false abuse complaints as a tool to gain a competitive advantage during custody disputes.

There is ample evidence to indicate that the filing of false abuse allegations during custody disputes has severe emotional, social, and mental health consequences for the child, for the targeted parent (mostly, but not exclusively, the father), as well as for the parent who filed the false allegation (as mediated through the increasingly disturbed behaviors of the child who served as the tool for the false allegation). Through proactive interventions, both the domestic violence industry and the divorce industry have the opportunity to better serve the best interests of the child by reducing false abuse allegations. Such proactive interventions would maintain the falsely accused parent (again, most commonly, but not exclusively, the father) as an important figure in the human ecology of the child (Farrell, 2001; Finley, 2001; Tong, 2002).

The interventions suggested above have the possibility of reinvigorating and enhancing postdivorce father child relationships. They contain the seeds of hope for improving the quality of life and well-being of all members of the former family triad - children, fathers, and mothers - as well as facilitating the transition to the uncertainties of postdivorce family life.

References and further reading

Amato, Paul R. 2000. “The Consequences of Divorce for Adults and Children.” Journal of

Marriage and the Family 62: 1269-1287.

Booth, Alan. 1999. “Causes and Consequences of Divorce: Reflections on Recent Research.”

Pp. 29-48 in The Postdivorce Family. Edited by Ross A. Thompson and Paul R. Amato. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Braver, Sanford L., and Diane O’Connell. 1998. Divorced Dads: Shattering the Myths. New

York: Tarcher/Putnam.

Emery, Robert E. 1999. “Postdivorce Family Life for Children: An Overview of Research and

Some Implications for Policy.” Pp. 3 - 27 in The Postdivorce Family. Edited by Ross A.

Thompson and Paul R. Amato. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Farrell, Warren. 2001. Father and Child Reunion: How to Bring the Dads We Need to the

Children We Love. New York: Tarcher/Putnam.

Finley, Gordon E. 2001. “Reduce false-abuse reports.” The Miami Herald, December 28, 2001,

p. 6B.

Finley, Gordon E. and Seth J. Schwartz. 2001. “Father Hunger, Divorce, Family Court, and the

Reconstruction of the Essential Father.” Poster presented at the meetings of the Society for Research in Child Development, Minneapolis, MN.

Hetherington, E. Mavis and Margaret M. Stanley-Hagan. 1997. “The Effects of Divorce on

Fathers and Their Children.” Pp. 191-211, 361-369 in The Role of the Father in Child

Development. 3rd ed. Edited by Michael E. Lamb. New York: Wiley.

Knox, David. 1998. The Divorced Dad’s Survival Book: How to Stay Connected with Your

Kids. New York: Plenum.

Parke, Ross D. and Armin A. Brott. 1999. Throwaway Dads: The Myths and Barriers That

Keep Men from Being the Fathers They Want to Be. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Silverstein, Louise B. and Carl F. Auerbach. 1999. “Deconstructing the Essential Father.”

American Psychologist 54: 397-407.

Thompson, Ross A. 1994. “The Role of the Father after Divorce.” Pp. 210-235 in The Future of

Children. Vol. 4, no. 1, Children and Divorce. San Francisco: Center for the Future of Children.

Tong, Dean. 2002. Elusive Innocence: Survival Guide for the Falsely Accused. Lafayette, LA:

Huntington House Publishers.

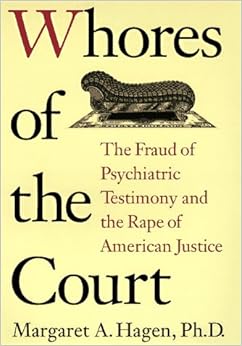

From the high-profile murder trials of the Menendez brothers and Jeffrey Dahmer to personal injury, product liability and child custody cases, lawyers across the country have increasingly turned to "expert" testimony from psychologists, psychiatrists and social workers to influence the decisions of judges and juries.

Psychologist Margaret Hagen, a professor and medical industry insider, details the very real danger of this booming business. In every state, a child can be taken away from a parent on the strength of five minutes of "neutral" testimony from a social worker. A criminal suspect's freedom or incarceration can depend on a superficial psychological examination performed by an incompetent, overworked, or, at worst, paid-off psychologist. Parole hearings hinge on the testimony of similarly incomplete or fraudulent evaluations, allowing "rehabilitated" violent criminals back onto the street to commit more heinous crimes, with no accountability for the reviewing "expert." Unmasking some legal psycho-expertise as a total fraud, Dr. Hagen instructs readers to protect themselves and their families from being victimized by psychological testimony in the courtroom. In today's frenzied legal climate, her insight and wisdom make for provocative, compelling and invaluable reading

We've been rope-a-doped by dopes!

ReplyDeleteIt's oppression & civil rights abuse101! Here's the problem with these family issues even being in court. No matter what happens, we're being exploited by the attorney clan with no possible resolution because there are no civil rights of Due Process anymore. 'Family' court is a spell of witchcraft that we've all bought into. It's an unconstitutoinal delusion.And it's obviously inhumane. And the courts won't do anything to change because then they'de by liable for criminal charges and civil lawsuits. This only reinforces the fact that the real head of government is #1 a broken court system, #2 a known deceptive practice, and #3 negative rights and unconscious rituals in control over we the people. In other words, and evil empire. (Satan couldn't have done it any better! Oh, ... wait, ... he did do this!) Here's the answer: uprightusa.org Educate justice with truth, love and honor. And make a righteous stand!

FLORIDA TODAY - OPINION

DeleteWritten by Gordon E. Finley, Ph.D., Miami

While I applaud columnist Paul Flemming for a sound review of the issues in Saturday’s “Alimony bill will be great — for lawyers,” his bottom-line conclusion is dead wrong.

The proposed state alimony reform bill will reduce litigation, not increase litigation. A bit of history: For years, the divorce vultures (a.k.a., the Family Law Section of the Florida Bar) have conned the Florida Legislature into writing divorce legislation that maximizes litigation and thus maximizes their income. In part, they have accomplished this by maximizing judicial discretion, which in practice means endless conflict and, of course, endless paid litigation.

No matter what they may say, the divorce vultures are interested only in one thing — maximizing their income.

I can irrefutably demonstrate this point with Flemming’s own words: “Thomas Duggar, an attorney in Tallahassee and a member of the Florida Bar’s Family Law Section, said last week at a Tallahassee Bar Association meeting that the section has a $100,000 war chest to sway public opinion against the legislation.”

Do your readers honestly believe they are spending all this money so they will lose income? The divorce vultures get the message in terms of what alimony reform will cost them — and save the children, fathers and mothers of divorce. I regret Mr. Flemming did not do the same.

Full Disclosure: I am an alimony-paying divorced father of two young adult daughters and retired university divorce researcher with multiple research and scholarly publications on this topic.

“Justice is a part of the human makeup. And if you deprive a person of Justice on a continuous basis, it’s really an attack (and not to get religious or anything) but it’s an attack on the human soul. We have, as societies, evolved ideas of Justice and we have done that because human nature needs Justice and it needs resolution. And if you deprive somebody of that long enough they’re going to have reactions…”

ReplyDelete~ Juli T. Star-Alexander – Executive Director, Redress, Inc.

Redress, Inc. 501c3 nonprofit corporation, created to combat corruption. Our purpose is to provide real assistance and solutions for citizens suffering from injustices. We operate as a formal business, with a Board of Directors guiding us. We take the following actions to seek redress: Competently organize as citizens working for the enforcement of our legal rights. Form a coalition so large and so effective that the authorities can no longer ignore us. We support and align with other civil rights groups and get our collective voices heard. Work to pass laws that benefit us and give us the means to fight against corruption, as is our legal right, and we work to repeal laws that are in violation of our legal rights. Become proactive in the election process, by screening of political candidates. As individuals, we support those who are striving to achieve excellence, and show how to remove from office those who have failed to get the job done. Make our presence known through every legal means. We monitor our courts and judges. We petition our government representatives for the assistance they are bound to provide us. We publicize our cases and demand redress. Create a flow of income that enables us to fight back in court, and to assist our members impoverished by the abuses inflicted on us. Create the means to relieve the stresses on us, as we share information and support each other. We become legal advocates for each other; we become an emotional support network for each other; we problem solve for individuals on a group basis! Educate our judges, lawyers, court personnel, law enforcement personnel and elected leaders about our rights as citizens! Actively work to eliminate incompetence, bias/prejudice, special relationships and corruption at all levels of government! Work actively with all media sources, to shed light on our efforts. It is reasonable to expect that if the authorities know we are watching and documenting, that their behaviors will improve. IT'S A HUGE TASK! Accountability will not happen overnight. But we believe that through supporting each other, we support ourselves. This results in a voice for justice and redress that cannot be ignored. Please become familiar with our web site, and feel free to call. We need each other - help us to help you! Although we are beginning operations in Nevada, we intend to extend into each state in a competent fashion. We are NOT attorneys, unless individual attorneys join us as members. We are simply people helping people. For those interested, we do not engage in the practice of law. You might be interested in this article Unauthorized Practice of Law on the Net. Call Redress, Inc. at 702.597.2982 or e-mail us at Redress@redressinc.com. WORKING TOGETHER TO ATTAIN FAIRNESS

PRO SE RIGHTS:

ReplyDeleteSims v. Aherns, 271 SW 720 (1925) ~ "The practice of law is an occupation of common right."

Brotherhood of Trainmen v. Virginia ex rel. Virginia State Bar, 377 U.S. 1; v. Wainwright, 372 U.S. 335; Argersinger v. Hamlin, Sheriff 407 U.S. 425 ~ Litigants can be assisted by unlicensed laymen during judicial proceedings.

Conley v. Gibson, 355 U.S. 41 at 48 (1957) ~ "Following the simple guide of rule 8(f) that all pleadings shall be so construed as to do substantial justice"... "The federal rules reject the approach that pleading is a game of skill in which one misstep by counsel may be decisive to the outcome and accept the principle that the purpose of pleading is to facilitate a proper decision on the merits." The court also cited Rule 8(f) FRCP, which holds that all pleadings shall be construed to do substantial justice.

Davis v. Wechler, 263 U.S. 22, 24; Stromberb v. California, 283 U.S. 359; NAACP v. Alabama, 375 U.S. 449 ~ "The assertion of federal rights, when plainly and reasonably made, are not to be defeated under the name of local practice."

Elmore v. McCammon (1986) 640 F. Supp. 905 ~ "... the right to file a lawsuit pro se is one of the most important rights under the constitution and laws."

Federal Rules of Civil Procedures, Rule 17, 28 USCA "Next Friend" ~ A next friend is a person who represents someone who is unable to tend to his or her own interest.

Haines v. Kerner, 404 U.S. 519 (1972) ~ "Allegations such as those asserted by petitioner, however inartfully pleaded, are sufficient"... "which we hold to less stringent standards than formal pleadings drafted by lawyers."

Jenkins v. McKeithen, 395 U.S. 411, 421 (1959); Picking v. Pennsylvania R. Co., 151 Fed 2nd 240; Pucket v. Cox, 456 2nd 233 ~ Pro se pleadings are to be considered without regard to technicality; pro se litigants' pleadings are not to be held to the same high standards of perfection as lawyers.

Maty v. Grasselli Chemical Co., 303 U.S. 197 (1938) ~ "Pleadings are intended to serve as a means of arriving at fair and just settlements of controversies between litigants. They should not raise barriers which prevent the achievement of that end. Proper pleading is important, but its importance consists in its effectiveness as a means to accomplish the end of a just judgment."

NAACP v. Button, 371 U.S. 415); United Mineworkers of America v. Gibbs, 383 U.S. 715; and Johnson v. Avery, 89 S. Ct. 747 (1969) ~ Members of groups who are competent nonlawyers can assist other members of the group achieve the goals of the group in court without being charged with "unauthorized practice of law."

Picking v. Pennsylvania Railway, 151 F.2d. 240, Third Circuit Court of Appeals ~ The plaintiff's civil rights pleading was 150 pages and described by a federal judge as "inept". Nevertheless, it was held "Where a plaintiff pleads pro se in a suit for protection of civil rights, the Court should endeavor to construe Plaintiff's Pleadings without regard to technicalities."

Puckett v. Cox, 456 F. 2d 233 (1972) (6th Cir. USCA) ~ It was held that a pro se complaint requires a less stringent reading than one drafted by a lawyer per Justice Black in Conley v. Gibson (see case listed above, Pro Se Rights Section).

Roadway Express v. Pipe, 447 U.S. 752 at 757 (1982) ~ "Due to sloth, inattention or desire to seize tactical advantage, lawyers have long engaged in dilatory practices... the glacial pace of much litigation breeds frustration with the Federal Courts and ultimately, disrespect for the law."

Sherar v. Cullen, 481 F. 2d 946 (1973) ~ "There can be no sanction or penalty imposed upon one because of his exercise of Constitutional Rights."

Schware v. Board of Examiners, United State Reports 353 U.S. pages 238, 239. ~ "The practice of law cannot be licensed by any state/State."